Commercial Construction Type Calculator

Project Details

Construction Type Recommendation

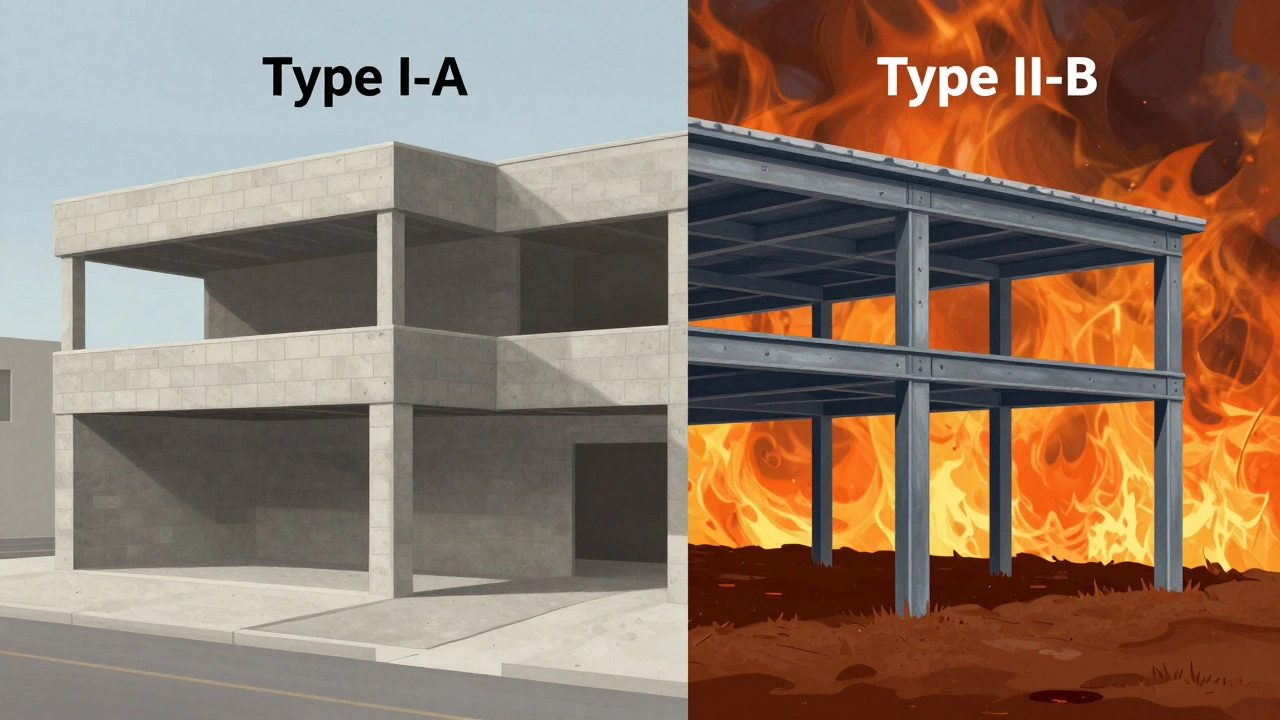

When you hear type A and type B construction, it’s not about quality or cost-it’s about safety. In commercial buildings, these classifications determine how long a structure can hold up in a fire, what materials you’re allowed to use, and whether your project will pass inspection. If you’re planning a retail space, office building, or warehouse, understanding the difference between Type A and Type B construction isn’t optional. It’s the line between getting a permit and facing a shutdown.

What Exactly Are Type A and Type B Construction?

Type A and Type B construction are part of the International Building Code (IBC), used across the U.S. and Canada. They fall under the broader category of building construction types, which classify structures based on fire resistance and material composition. Think of it like a safety rating system for buildings. Type A is the most fire-resistant. Type B is still safe, but with fewer restrictions on combustible materials.

The difference comes down to three things: the materials used, how long structural elements can survive fire, and where the building is allowed to be built. Type A construction requires non-combustible materials like steel, concrete, and masonry. Type B allows limited use of wood or other combustibles, but only if they’re protected by fire-resistant coatings or assemblies.

Type A Construction: The Gold Standard

Type A construction is divided into Type I-A and Type I-B. Both use non-combustible materials, but Type I-A has higher fire-resistance ratings. For example:

- Type I-A: Structural elements must withstand fire for at least 3 hours

- Type I-B: Structural elements must withstand fire for at least 2 hours

You’ll find Type I-A in high-rise office towers, hospitals, and large shopping centers. These buildings need to protect hundreds or thousands of people. If a fire breaks out, the structure has to stay standing long enough for full evacuation and firefighter access. That’s why steel beams are encased in concrete, floors are poured with reinforced concrete, and walls are built with masonry blocks.

In Vancouver, where building codes are strict and population density is high, most new commercial projects over four stories are required to be Type I-A. A 2023 fire safety audit by the City of Vancouver showed that 92% of commercial buildings constructed after 2020 met Type I-A standards.

Type B Construction: Where Practical Meets Code

Type B construction includes Type II-A and Type II-B. Like Type A, these use non-combustible materials for the main structure, but they allow more flexibility in fire-resistance ratings.

- Type II-A: Structural elements must resist fire for at least 1 hour

- Type II-B: No minimum fire-resistance requirement for structural elements

Type II-A is common in smaller retail spaces, medical clinics, and office buildings under 50 feet tall. It’s the sweet spot for many developers-safe enough to meet code, but cheaper and faster to build than Type I.

Type II-B is where things get tricky. You can use steel frames and concrete floors, but without fireproofing, those materials can still fail faster in a fire. That’s why Type II-B is only allowed in buildings with lower occupancy, like small warehouses or storage facilities. In Vancouver, you can’t use Type II-B for any building that holds more than 50 people at once.

Why It Matters for Your Project

Choosing the wrong construction type can cost you time, money, and even your business. Here’s what happens when you get it wrong:

- You apply for a permit using Type II-B, but the city requires Type I-A because of your building’s size or use. Your plans get rejected. You lose 6-8 weeks.

- You build with wood framing under the assumption it’s allowed. The fire marshal shuts you down during inspection. You pay to tear it out and rebuild.

- You skip fireproofing to save $20,000. Later, your insurance denies a claim because the building didn’t meet code.

One Vancouver-based developer lost $187,000 in 2024 after building a 12,000-square-foot retail space as Type II-B, thinking it was acceptable. The city later reclassified the space as a high-hazard occupancy due to the type of goods stored inside. The building had to be retrofitted to Type I-A before reopening.

What Materials Are Allowed?

Here’s a quick breakdown of what you can and can’t use:

| Material | Type I-A | Type I-B | Type II-A | Type II-B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steel beams | Yes, fireproofed | Yes, fireproofed | Yes, fireproofed | Yes, no fireproofing |

| Concrete floors | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wood framing | No | No | No | No |

| Fire-rated drywall | Required | Required | Required | Optional |

| Plastic insulation | Only if fire-rated | Only if fire-rated | Only if fire-rated | Prohibited |

Notice that wood framing isn’t allowed in any Type A or Type B construction for commercial buildings. That’s a common misconception. Even if you’re building a small storefront, you can’t use 2x4s for load-bearing walls. You need steel studs or concrete block. The only exception is for non-load-bearing partitions in Type II-B, and even then, they must be covered with fire-rated drywall.

How to Decide Which Type to Use

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Your choice depends on:

- Building height and area - Buildings over 75 feet or 10,000 sq ft usually require Type I-A.

- Occupancy type - Hospitals, schools, and theaters need higher fire resistance than storage units.

- Location - Dense urban areas like downtown Vancouver or downtown Toronto have stricter rules than rural zones.

- Future use - If you plan to sell or lease the building later, Type I-A adds resale value.

As a rule of thumb: if you’re unsure, go with Type I-A. It’s more expensive upfront-about 15-20% higher in material and labor costs-but it avoids costly delays and rework. In 2025, 78% of commercial builders in British Columbia started with Type I-A plans, even for smaller projects, because they knew it saved time in the long run.

What Happens After Construction?

Once the building is up, inspections don’t stop. Fire marshals conduct random checks. Insurance companies audit compliance. If your building doesn’t match the approved construction type, your policy can be voided.

Also, if you ever want to expand, change the use, or add floors, you may need to upgrade to a higher construction type. A small retail space built as Type II-A that becomes a restaurant or daycare might suddenly need Type I-A. That’s not a minor renovation-it’s a full structural overhaul.

Common Myths About Type A and Type B

Here are three myths that trip up builders:

- Myth: Type B means lower quality. Truth: Type II-A is perfectly safe for many uses. It’s not inferior-it’s appropriate.

- Myth: You can use wood if it’s treated. Truth: Fire-retardant-treated wood is still combustible. It’s not allowed in load-bearing structures for commercial buildings.

- Myth: Type A is only for big cities. Truth: Even in small towns, if your building holds 50+ people, you’re likely required to use Type I-A or I-B.

Final Checklist Before You Break Ground

Before you submit your plans, run through this:

- Confirm your building’s occupancy classification with your local building department

- Check the maximum allowable height and area for each construction type in your zone

- Verify that all structural elements meet the required fire-resistance ratings

- Ensure your architect and contractor have experience with the specific type you’re using

- Get a pre-inspection review from the fire marshal if you’re unsure

Skipping any of these steps can cost you months-and thousands of dollars. In commercial construction, the smallest code violation can become the biggest liability.

Is Type A construction always more expensive than Type B?

Yes, typically. Type I-A uses more steel, concrete, and fireproofing, which raises material and labor costs by 15-25% compared to Type II-B. But it often saves money long-term by avoiding delays, rework, and insurance issues. For many projects, the higher upfront cost is worth the peace of mind.

Can I use wood in Type B construction?

No. Even Type II-B, the least restrictive of the Type B classifications, prohibits wood framing in load-bearing walls or structural elements in commercial buildings. Non-load-bearing partitions can use wood if covered with fire-rated drywall, but the main structure must be non-combustible-steel, concrete, or masonry.

What’s the difference between Type I-A and Type I-B?

Type I-A requires structural elements to withstand fire for at least 3 hours. Type I-B requires 2 hours. Type I-A is used in high-rise buildings, hospitals, and large public spaces where evacuation takes longer. Type I-B is common in mid-rise office buildings and hotels where the risk profile is lower.

Do I need a special permit for Type A construction?

You don’t need a special permit just because it’s Type A. But you do need detailed engineering plans showing fire-resistance ratings for every structural element. These plans must be reviewed and stamped by a licensed structural engineer and fire protection specialist. The permit process is longer, not because of the type, but because of the complexity of the plans.

Can I downgrade from Type A to Type B to save money?

No. Building codes require you to use the highest construction type based on your building’s height, area, and occupancy. You can’t choose a lower type just to cut costs. If your building qualifies for Type I-A, you must build to that standard. Attempting to downgrade can lead to permit denial, fines, or forced demolition.

If you’re planning a commercial project, don’t guess your construction type. Talk to your local building department early. Bring your site plan, occupancy estimate, and square footage. Ask them: "What’s the minimum construction type required for this use?" That simple question can save you from costly mistakes.